Innovation

Ground effect in F1: How aviation pioneers sparked a motorsport revolution

by David Tremayne

9min read

Wings have been familiar on racing cars since the mid-1960s, and would eventually lead to full ground effect in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, and again on today’s F1 cars.

So how did something aeronautical become applied to race cars?

Lotus Cars founder Colin Chapman found success in applying principles from aviation - principles that were established centuries before they shaped motorsport engineering.

In the mid-1700s Dutch-born, Swiss-based doctor, physician and mathematician Daniel Bernoulli was especially interested in fluid dynamics and is best remembered for his theorem that any increase in the velocity of a flow of air is accompanied by a reduction in that air’s pressure. Effectively, he had encapsulated the law of physics that would later govern flight.

An aircraft wing has an aerofoil camber on the top which makes the air speed up to travel across a distance that is greater than its underside. That increase in air velocity creates a reduction in pressure; the flow beneath the wing has a shorter distance to travel and therefore has a relatively higher pressure and this is what causes the wing to lift. Turn that wing upside down, and you create the opposite effect – negative lift or, in the case of a race car, what became better known as downforce. Ground effect is what happens when that wing runs very close to an influential boundary such as the ground itself, which helps to influence the airflow further.

The roots of F1 ground effect

Bernoulli died in 1782, long before suitable power sources existed. Then, in 1846, Sir George Cayley defined the concept of the fixed-wing aircraft. But it are not until that was validated when the Wright Brothers first flew at Kitty Hawk, on December 17th, 1903, that flight was attained.

Fritz von Opel, together with Max Valier and Friedrich Wilhelm Sander, was believed to be the first to apply an inverted airplane wing to a racing car. His Opel RAK 2 was powered by 24 rockets and at Avus on May 23rd 1928 attained 145 mph.

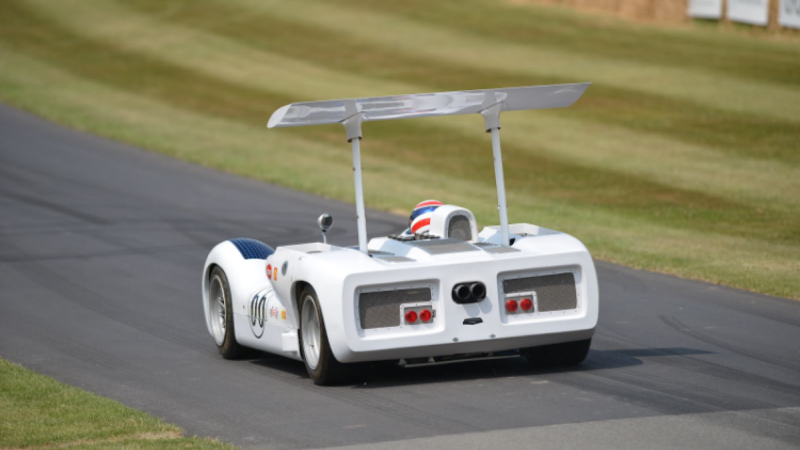

Swiss racer Michael May fitted an inverted overhead wing to his Porsche 550 Spyder for the 1956 Nurburgring 1000 kms, and in 1965 McLaren designer Robin Herd trialled a similar device on the experimental McLaren M2A, admitting to the author that it achieved a three-second reduction in lap time and made the car much more stable, but was mothballed because of more pressing projects. In 1966 the brilliant Jim Hall successfully applied a similar device to his CanAm Chapparal 2Es (below), and subsequently, his World Sportscar Championship 2F demonstrated its value to a European audience.

Why don’t we make the whole car an inverted wing…?

Peter Wright

, Aerodynamicist

Gallery

At Riverside in 1967 Jimmy Clark had a rare outing in a non-Lotus, leading in Rolla Vollstedt’s Indycar which impressed him with the resultant downforce from its experimental chassis-mounted rear spoiler/winglet. In the 1968 Tasman series he and mechanics Roger Porteous and Leo Wybrott experimented at Teretonga with the rotor blade from a helicopter mounted above his Lotus 49’s transmission. But Chapman ordered it to be removed. Thus, though the Lotus 49B appeared in Monaco with front winglets and a duck tail, it was the Ferrari 312 and the Brabham BT26 that were the first to wear rear wings in F1, at Spa soon afterwards. Chapman, typically, then introduced the huge and fragile overhead wings mounted on the rear uprights.

While aerofoils quickly became popular and effective, the development of full-blown ground effect was slower.

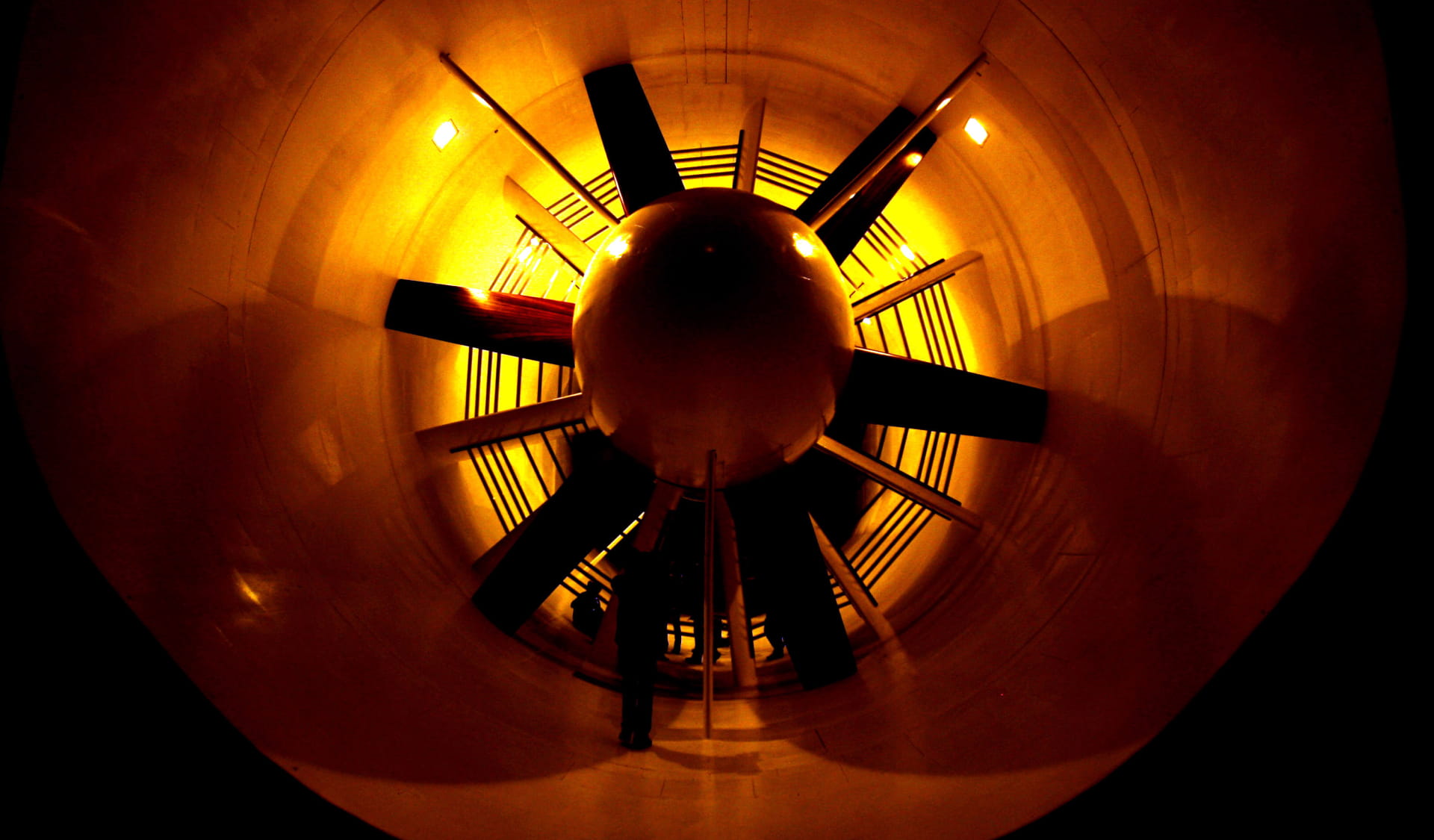

Auto Union began to experience the phenomena on its record-breaking streamliners of 1938, but it wasn’t until 1968, in separate investigations in South America and the UK, that ground effect development proceeded once again. In Argentina, far-sighted engineer Heriberto Pronello created his Huayra Pronello Ford racing coupe which, it only transpired publicly after runs at the UK’s Caseby Wind Tunnel last year, had the same airflow expansion rate of one to five that aerodynamicists would decide was optimal on F1 cars 20 years later. In the UK, meanwhile, aerodynamicist Peter Wright at BRM was secretly developing a ‘wing car’.

BRM chief engineer Tony Rudd wrote: “One day in 1969 Peter said, ‘Why don’t we make the whole car an inverted wing…?’ And that’s what it was, but it didn’t have sideplates and it didn’t have skirts.”

In 1970 McLaren designer Herd added wing-shaped sidepods between the wheels of his March 701 (below), “though without endplates and skirts, their effect was negligible.”

The March 701 featured wing-shaped sidepods

When Chapman employed Rudd at Lotus and in 1975 gave him responsibility for turning his blueprint for a completely new F1 car into reality, Rudd enlisted Wright, and designers Ralph Bellamy and later Tony Southgate, to create what would become the 1977 Lotus 78. F1’s first ground effect car.

I’ve been called the ‘father of ground effect in F1’ by a few people, but I was never really a car designer

Peter Wright

, Aerodynamicist

“I’ve been called the ‘father of ground effect in F1’ by a few people, but I was never really a car designer,” Wright chuckles. “I’ve always been a research and development guy! And some of what I produced found its way onto an F1 car. The 78 was the one I was most significantly involved with.”

Bellamy came up with a very simple car, for which Wright designed some sidepods, but the real breakthrough came, “When we stumbled on the effect of sealing off the gap between the sidepods and the road with skirts. That’s when we got it all to work and all sorts of things started happening!”

The Lotus 79 took ground effect to new heights

“In those days, the normal downforce generated by a good car, like the Shadow DN5, was about 750 lbs at 150 mph,” Southgate reveals. “The Lotus 78 took that to 1250 lbs – a fantastic increase.”

The Lotus 78 redefined technical parameters with its phenomenal grip, and won seven grands prix in the hands of Mario Andretti, Gunnar Nilsson and Ronnie Peterson. But as the 1978 Lotus 79 placed all the fuel behind the driver and thus reduced drag through the sidepods, it took an even greater step forward and Andretti steered it to the world championship.

Chapman and his team didn’t invent wings or ground effect but undoubtedly embraced both best to release the downforce genie from its bottle, and generated wholesale change in the aerodynamic design and performance of race cars.

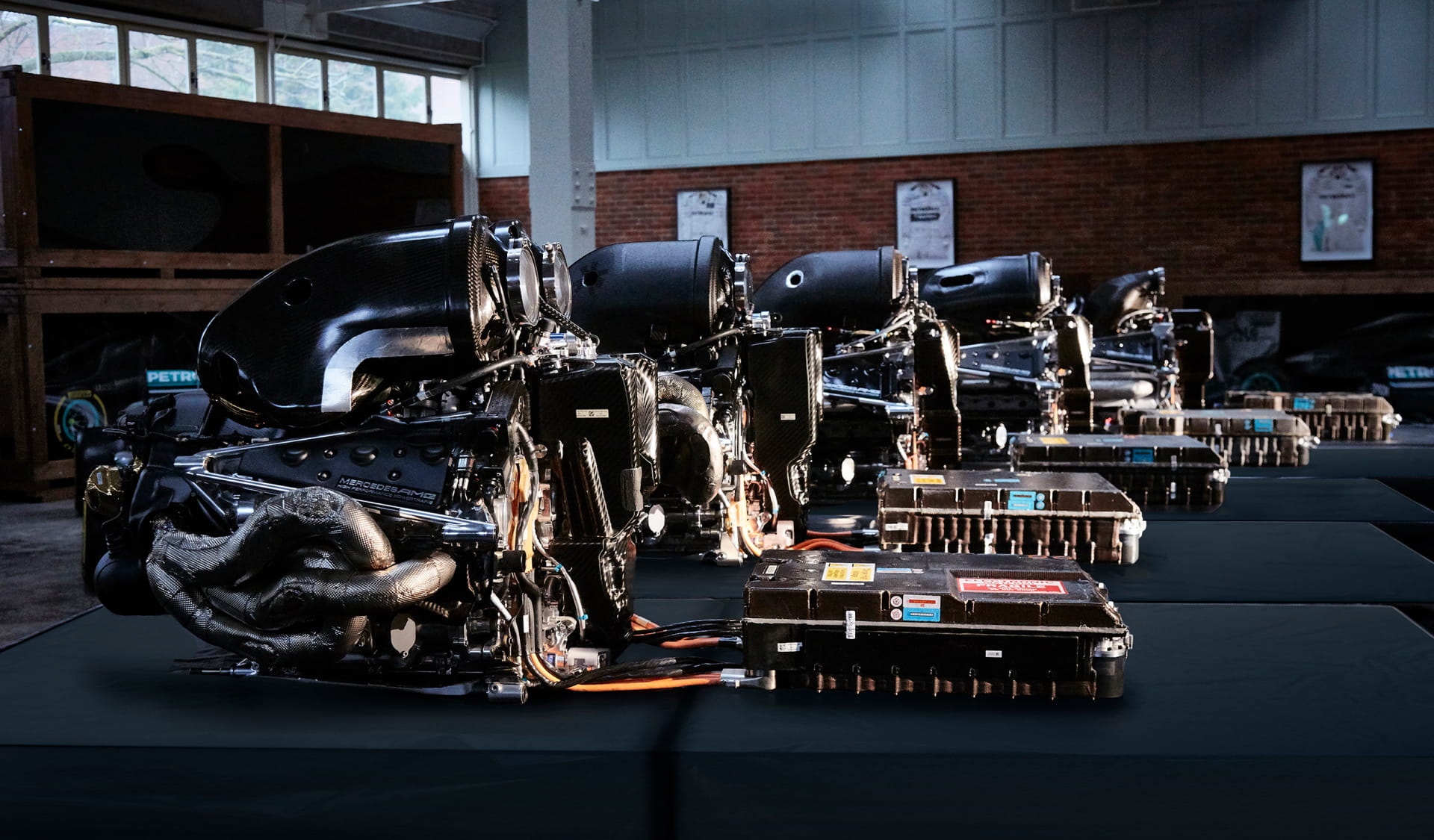

Rules would change, and skirts are no more, but ground effect couldn’t be disinvented. Wright’s brilliance left a legacy of intimate attention to undercar airflow and triggered an obsession with downforce that endures to this day.