Car

Formula 1: What is the Drag Reduction System and how does DRS work?

by Steve Rendle

5min read

.jpg?cx=0.62&cy=0.39)

The Drag Reduction System (DRS) is used as an overtaking aid in Formula 3, Formula 2, and Formula 1.

DRS will soon be phased out of F1 with the dawn of the upcoming 2026 regulations - but how, and why, was DRS implemented in the first place?

The need for overtaking solutions

Prior to the beginning of the current 1.6-litre hybrid power-unit F1 era, when 2.4-litre V8 engines were still in use, the sport began to receive widespread criticism due to a perceived lack of overtaking, which had led to somewhat processional races, arguably impacting audience figures.

In an effort to address those criticisms by improving overtaking opportunities, the sport’s governing body, the FIA, tasked its technical team with finding a workable solution that could be implemented consistently and fairly for all teams, via amendments to the technical regulations.

It was obvious that the difficulty in overtaking was primarily due to the reduction in downforce suffered by a challenger when running closely behind another car (or cars) in ‘dirty’ turbulent air.

Turbulent air significantly reduces the efficiency of a car’s aerodynamics, as the smooth, consistent airflow over the aerodynamic surfaces is disturbed, reducing downforce, which in turn affects both grip and braking levels.

After extensive research and consultation with teams, the result of the FIA’s investigations was the Drag Reduction System (DRS), first introduced to F1 from the start of the 2011 season.

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

McLaren test driver Oliver Turvey driving with DRS deployed (the rear wing flap open) during 2011 pre-season testing

How DRS Works

DRS and racing tactics

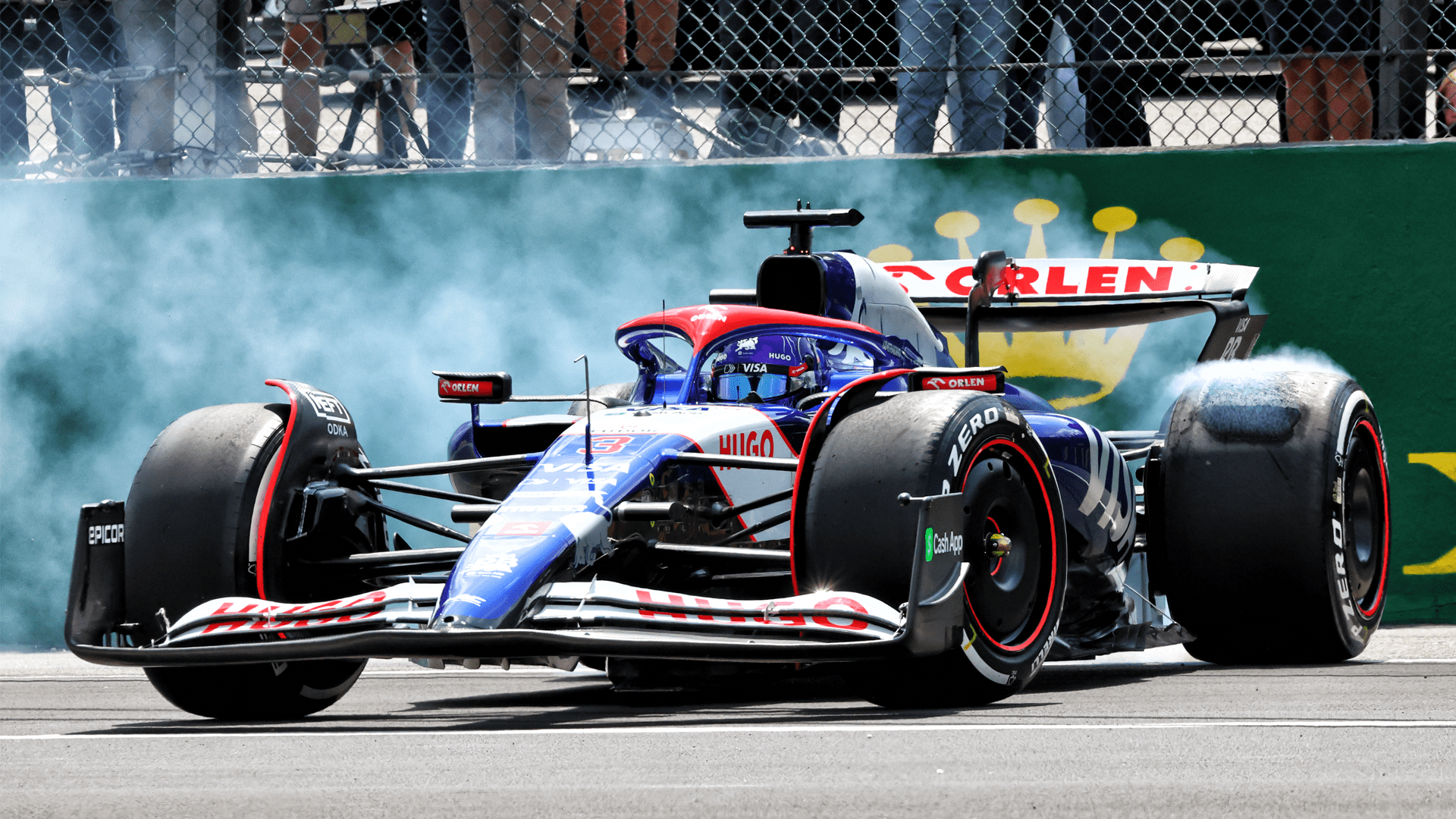

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

Williams driver Alex Albon leading a DRS train in the 2023 Canadian Grand Prix

The technical implementation of DRS in F1

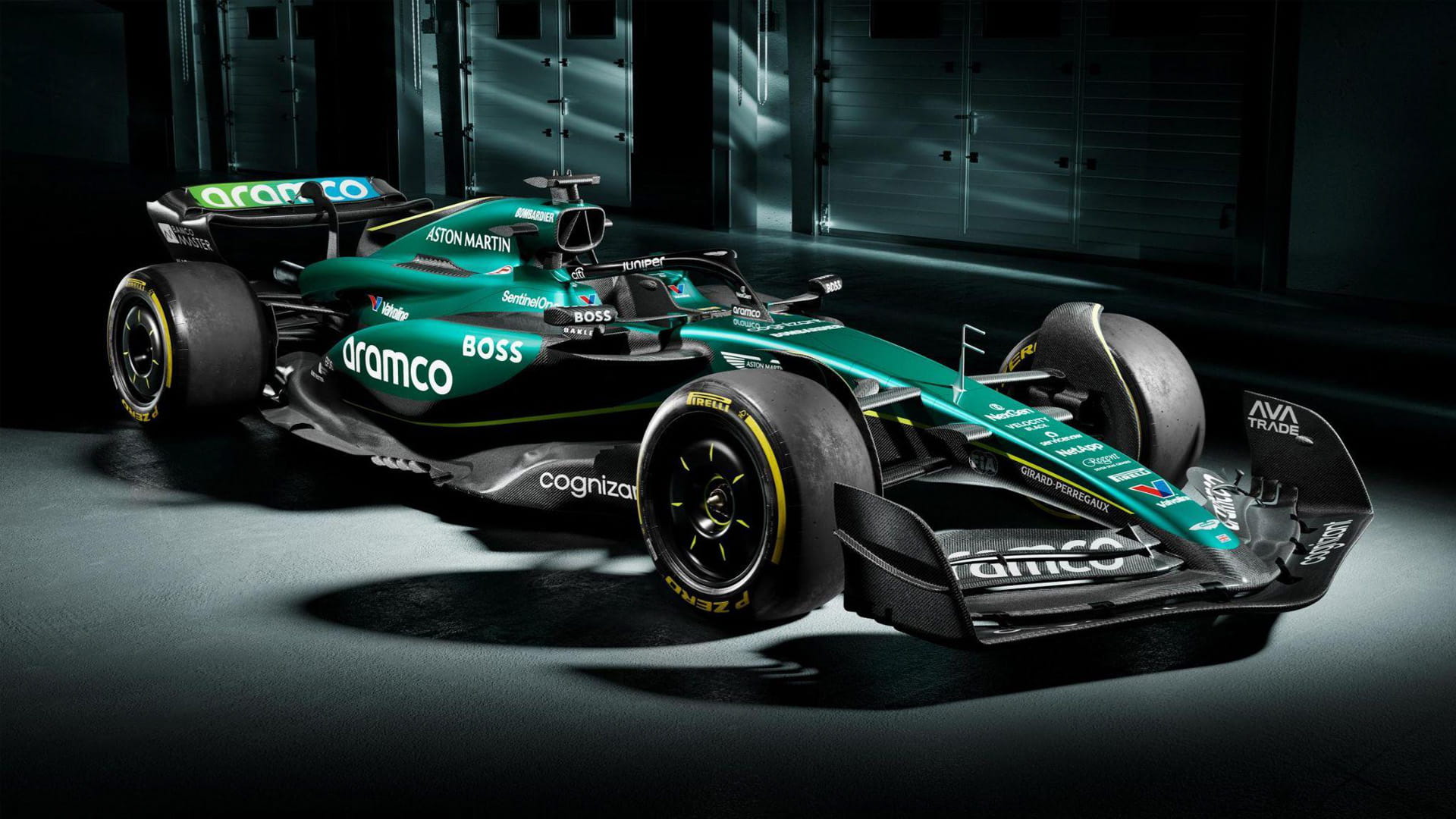

In the form adopted for F1, DRS reduces the angle of the upper rear wing element to reduce drag. The system must be manually operated by the driver using a button on the steering wheel.

The button sends a signal to the FIA standard electronic control unit (fitted to all cars), which relays the signal to an actuator mounted in the centre of the rear wing.

When activated, the actuator reduces the angle of the upper wing element to a pre-set ‘open’ position. The system is either ‘on’ or ‘off’ with the wing element either ‘open’ or ‘closed,’ with no intermediate positions possible.

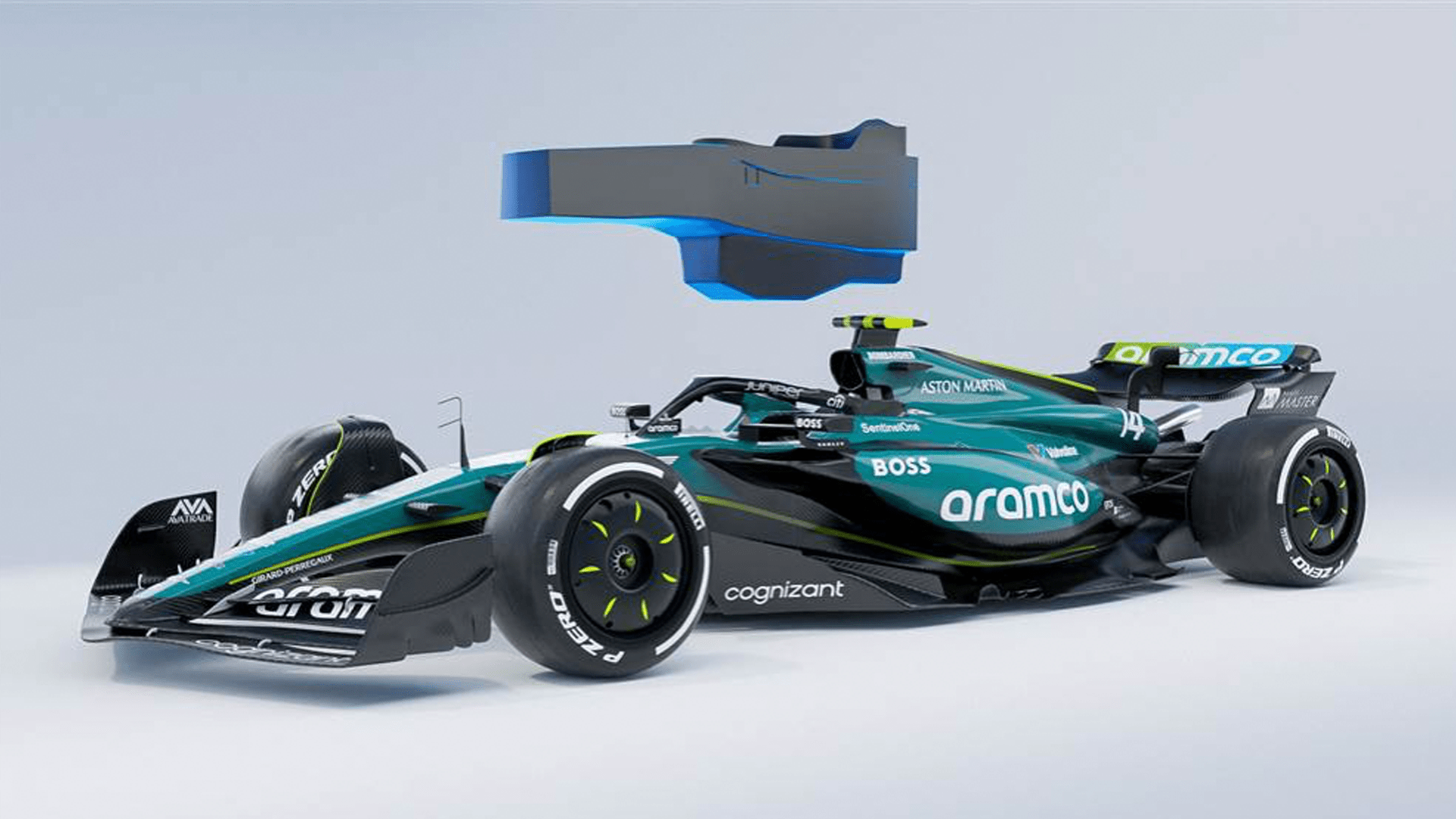

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

Render of an Aston Martin AMR24 with its rear wing open, simulating airflow and turbulence beyond the rear wing

The DRS 'failsafe'

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

Render of the rear wing of an Aston Martin AMR24 with DRS closed, simulating the airflow above and beyond the rear wing

DRS Activation zones and restrictions

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

A DRS sign showing a DRS activation zone at Silverstone

Exploitation of DRS by F1 teams

And in 2024, McLaren came under scrutiny as its rear wing - which was legal - flexed to the point that two 'flaps' opened the main plane of the wing at high speed, further reducing drag and giving the wing a 'DRS effect' without DRS being enabled. This wing was modified after the FIA requested the team to do so.

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

An illustration of the 'trick' McLaren rear wing that flexed enough to provide a DRS effect in high-speed sections before it was changed, after a request from the FIA

The expansion of DRS and its future in F1

Although originally introduced in F1, DRS has now filtered down to F2 and F3 cars, albeit running to slightly different regulations to suit those formulae. A variation on the system was also adopted by the DTM touring car series from 2013 until 2021.

So, has the concept worked? Well, in terms of achieving the ability to overtake, yes, though the use of DRS has proved controversial, with some purists viewing it as an ‘artificial’ means of passing.

Looking at the future of DRS in F1, the system will remain in use until a raft of new regulations is introduced for the 2026 season, which will result in redesigned, physically smaller cars that will use ‘X’ and ‘Z’ modes - a form of active aerodynamics using adjustable front and rear wings.

‘Z-mode’ will be the default mode and ‘X-mode’ a low-drag mode aimed at maximizing straight-line speed and improving overtaking opportunities. In the meantime, designers will aim to exploit the maximum potential offered by DRS.

/xpb_1300472_hires-(1).jpg?cx=0.52&cy=0.57)

/image-(2).jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)