Innovation

Formula 1 safety: How F1 drivers are protected from accidents

by Steve Rendle

5min read

Formula 1 is a dangerous sport. That’s a fact. The risk will never be completely eradicated, but, since the late 20th century, there has been a major focus on improving safety throughout motorsport.

Innovation

Ground effect in F1: How aviation pioneers sparked a motorsport revolution

The impact of Professor Sid Watkins

Professor Sid Watkins (R) with Michael Schumacher in 2005

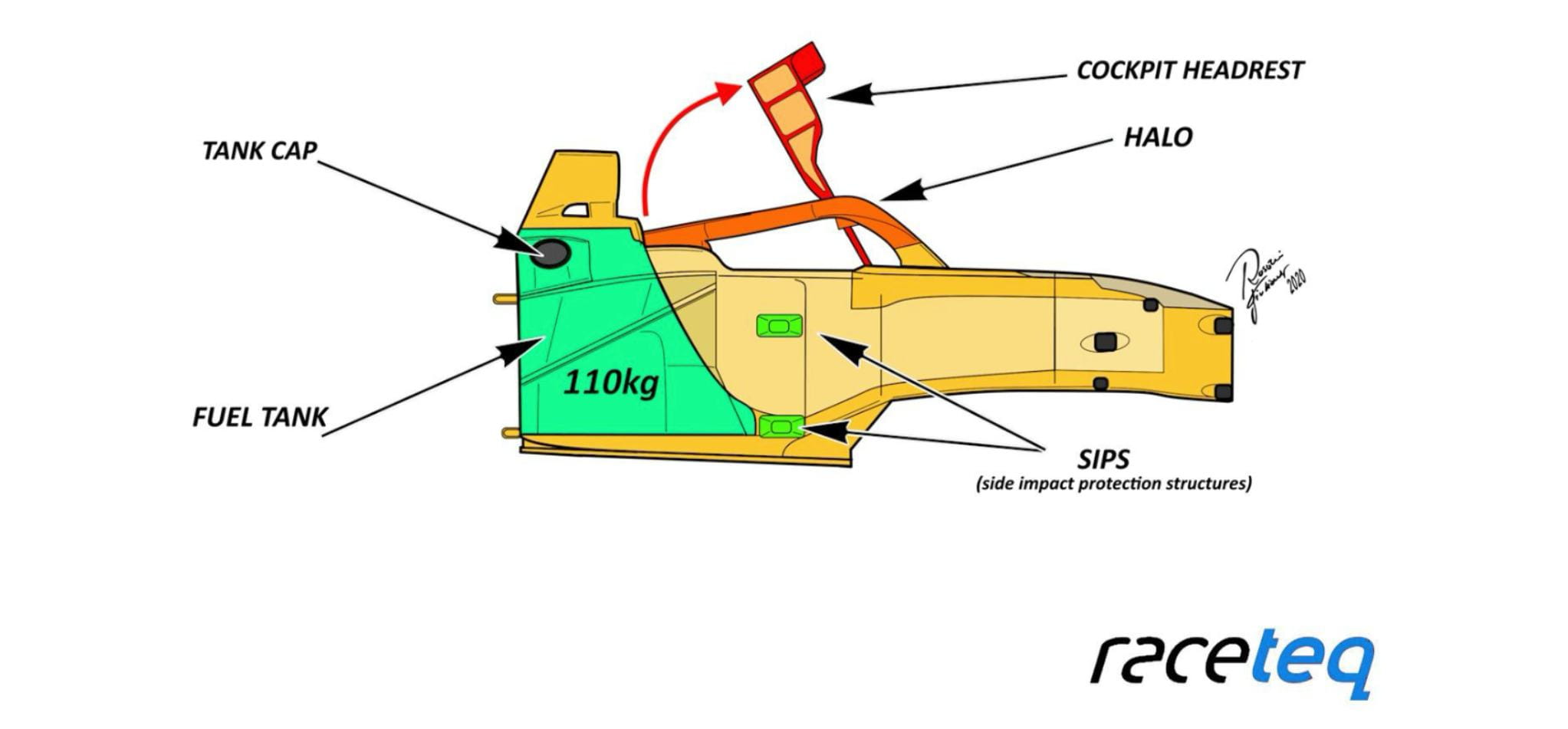

An illustration showing the layout of the crash structure that encompasses the driver and fuel tank in an F1 car

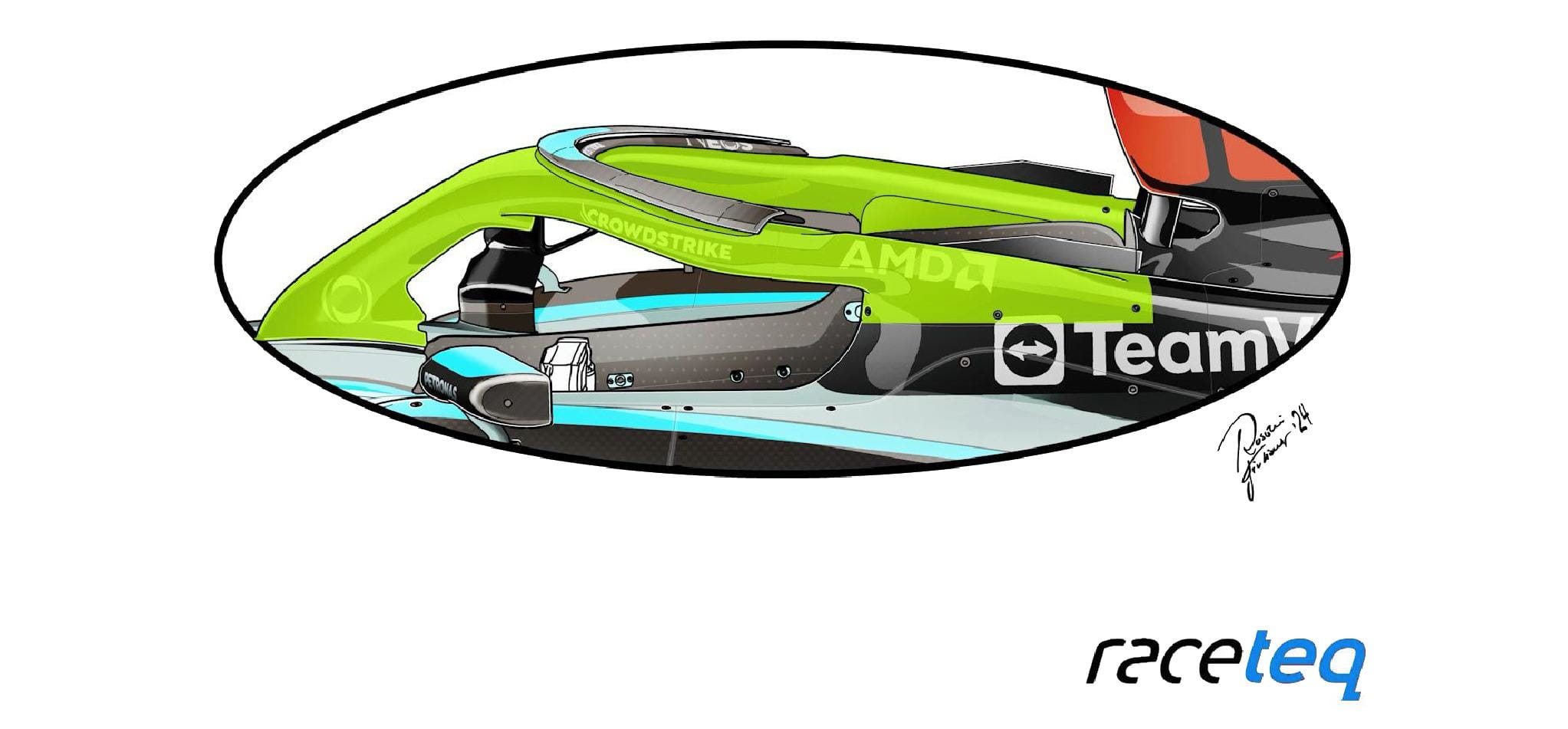

The halo device

An illustration of the halo, a standard component supplied to teams in order to protect the driver’s head from objects

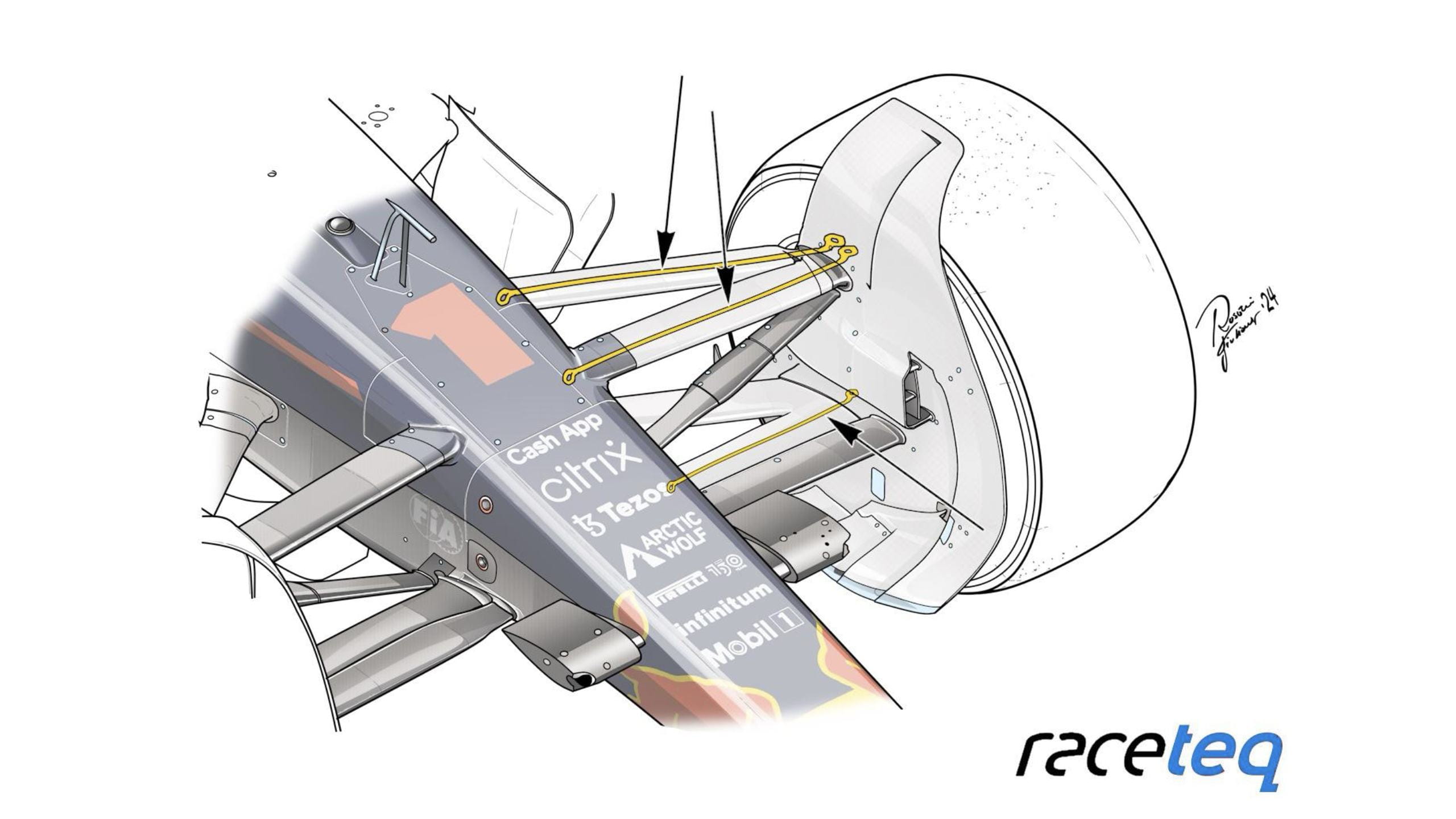

Formula 1 wheel tethers are located within the suspension wishbones as shown in this illustration

The role of crash structures

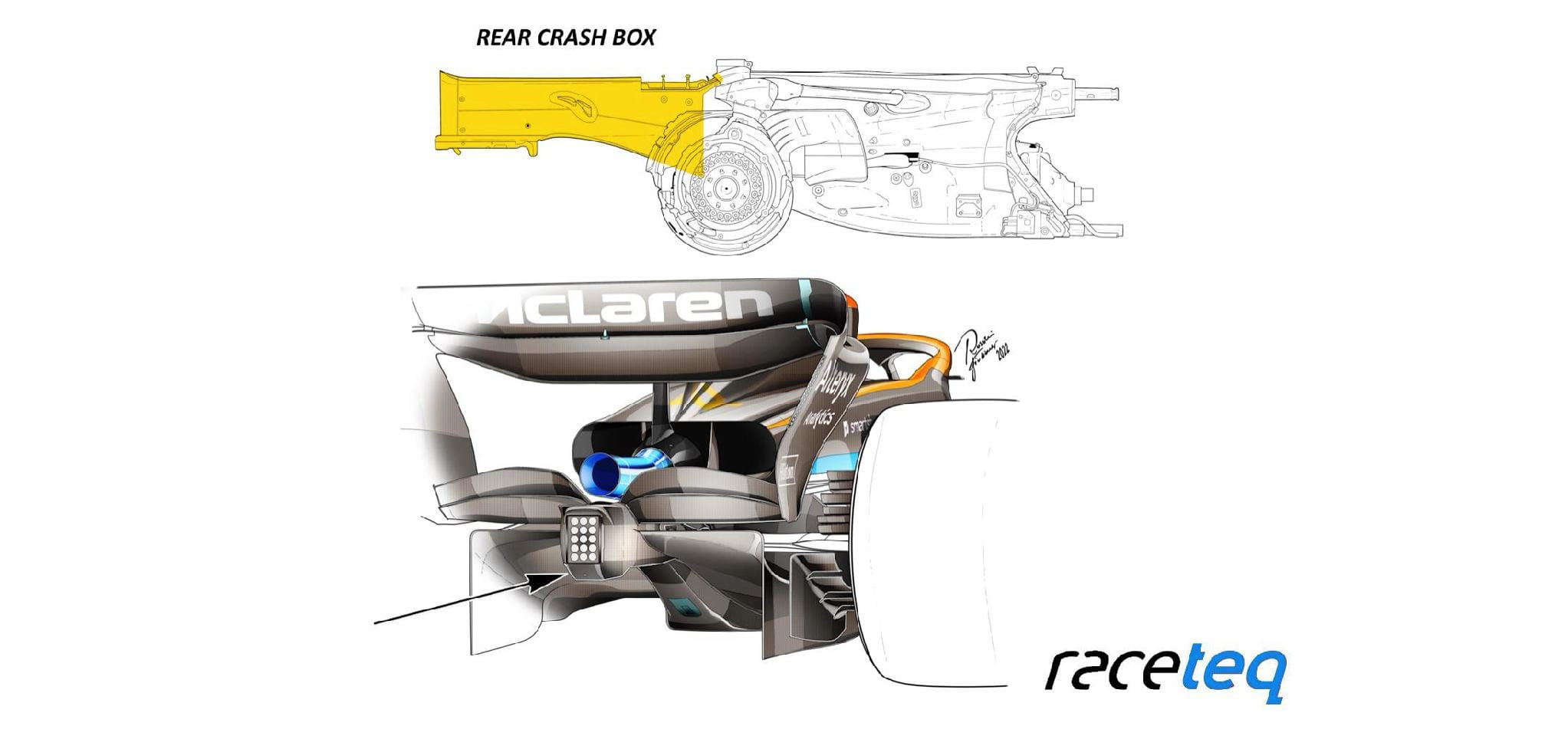

The rear crash structure or rear crash box protrudes behind the rear wheels

Aston Martin Aramco F1 driver Fernando Alonso wearing his race helmet and HANS device at the 2023 Las Vegas Grand Prix

The FIA Marshalling system allows Race Control to show virtual flags around the circuit and on drivers’ cockpit displays

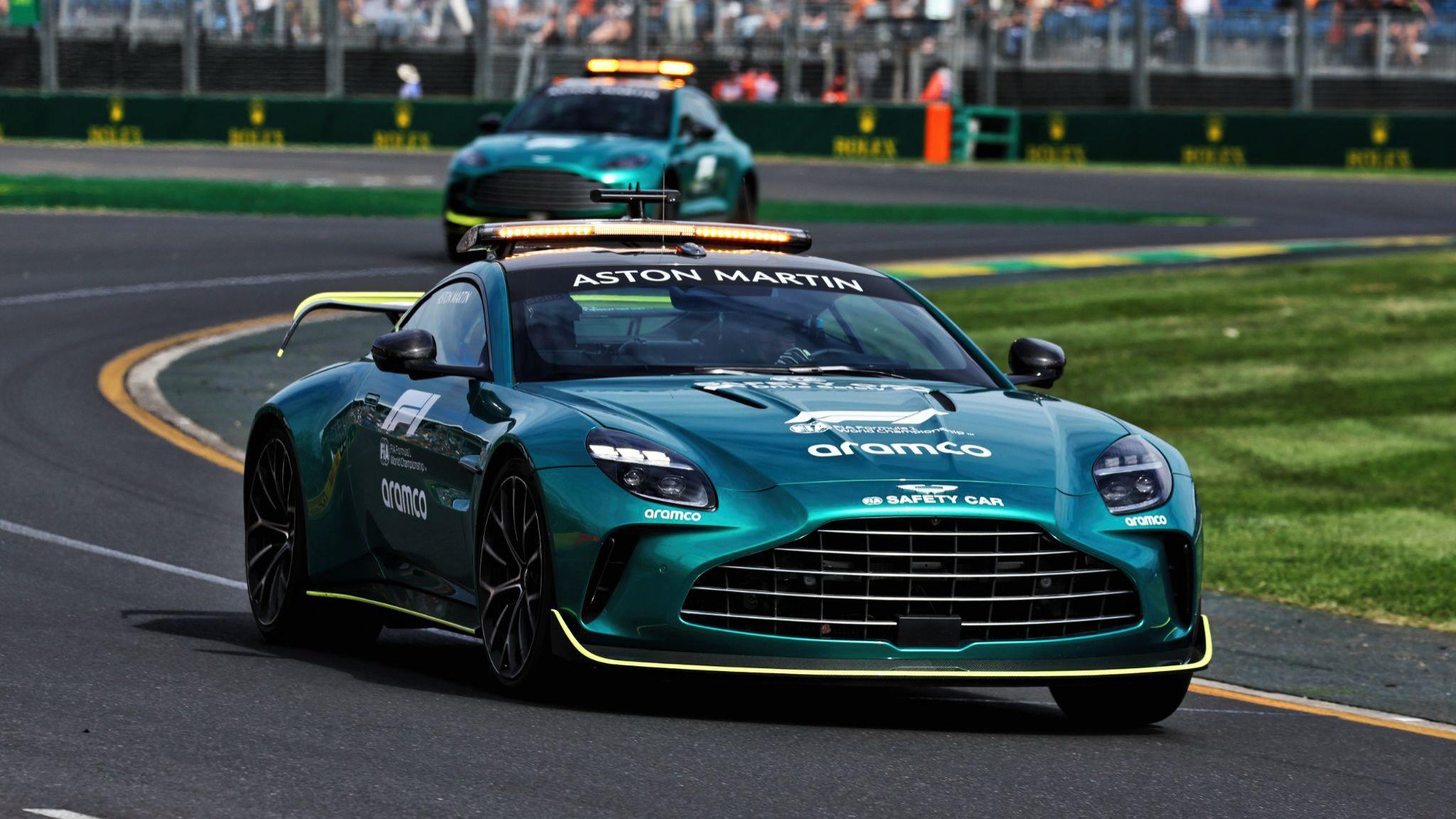

/image-(2).jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

.jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

/xpb_1300472_hires-(1).jpg?cx=0.52&cy=0.57)