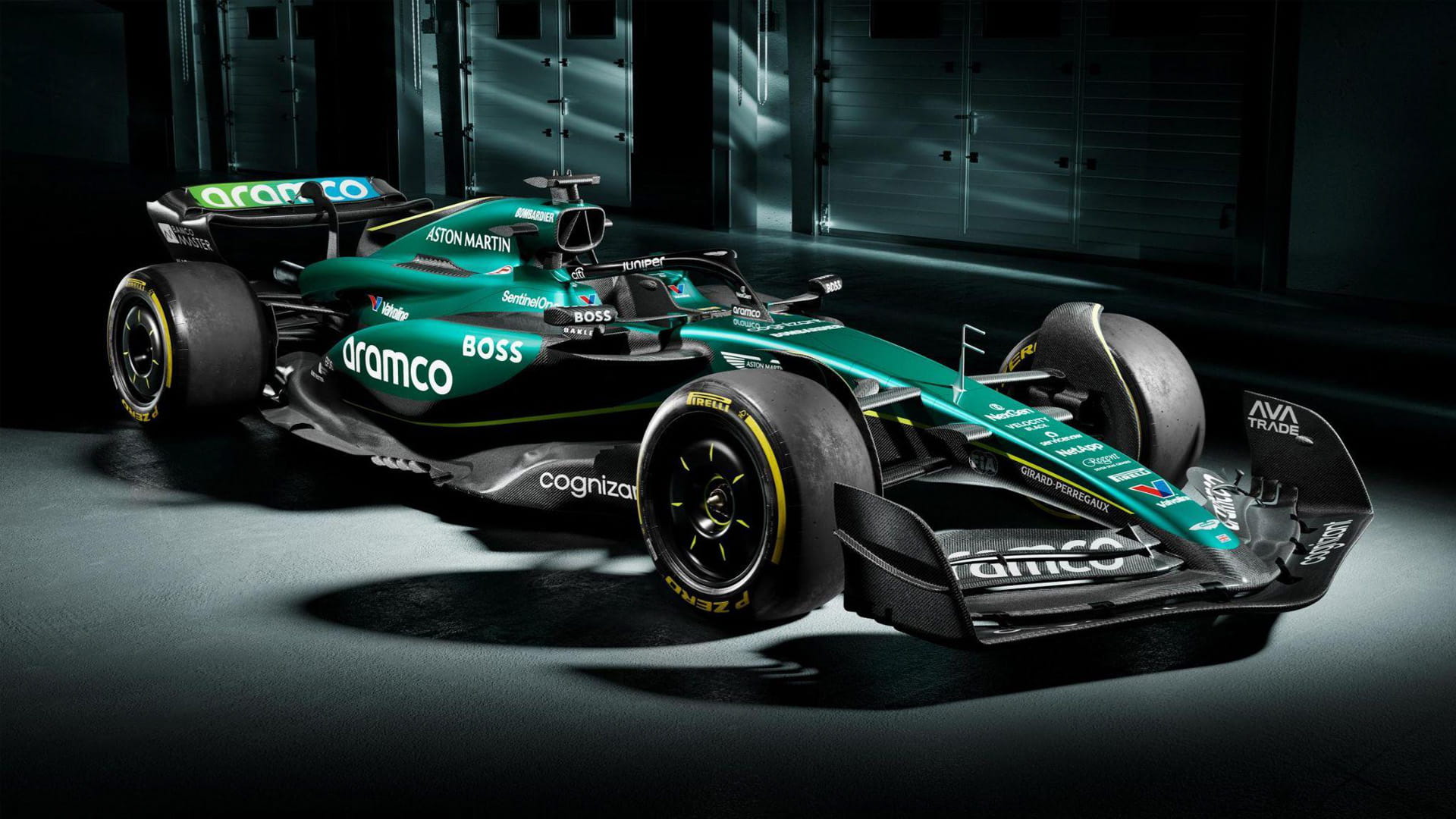

Car

How do windtunnels work - and how are they regulated in Formula 1?

by Rosario Giuliana

6min read

.png?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

Whether it’s a Formula 1 car screaming through Eau Rouge, a Le Mans Hypercar weaving through the Porsche Curves, or a stock car blazing around Daytona, the windtunnel is a crucial backbone to those motorsport spectacles.

Windtunnels have been used for decades in the study of aeronautical, aerospace and aerodynamic engineering - and they’re pivotal in the study of F1 cars’ behaviour.

But, why are windtunnels so important, why are they a powerful tool in understanding F1 aerodynamics - and why do they need to be so heavily regulated?

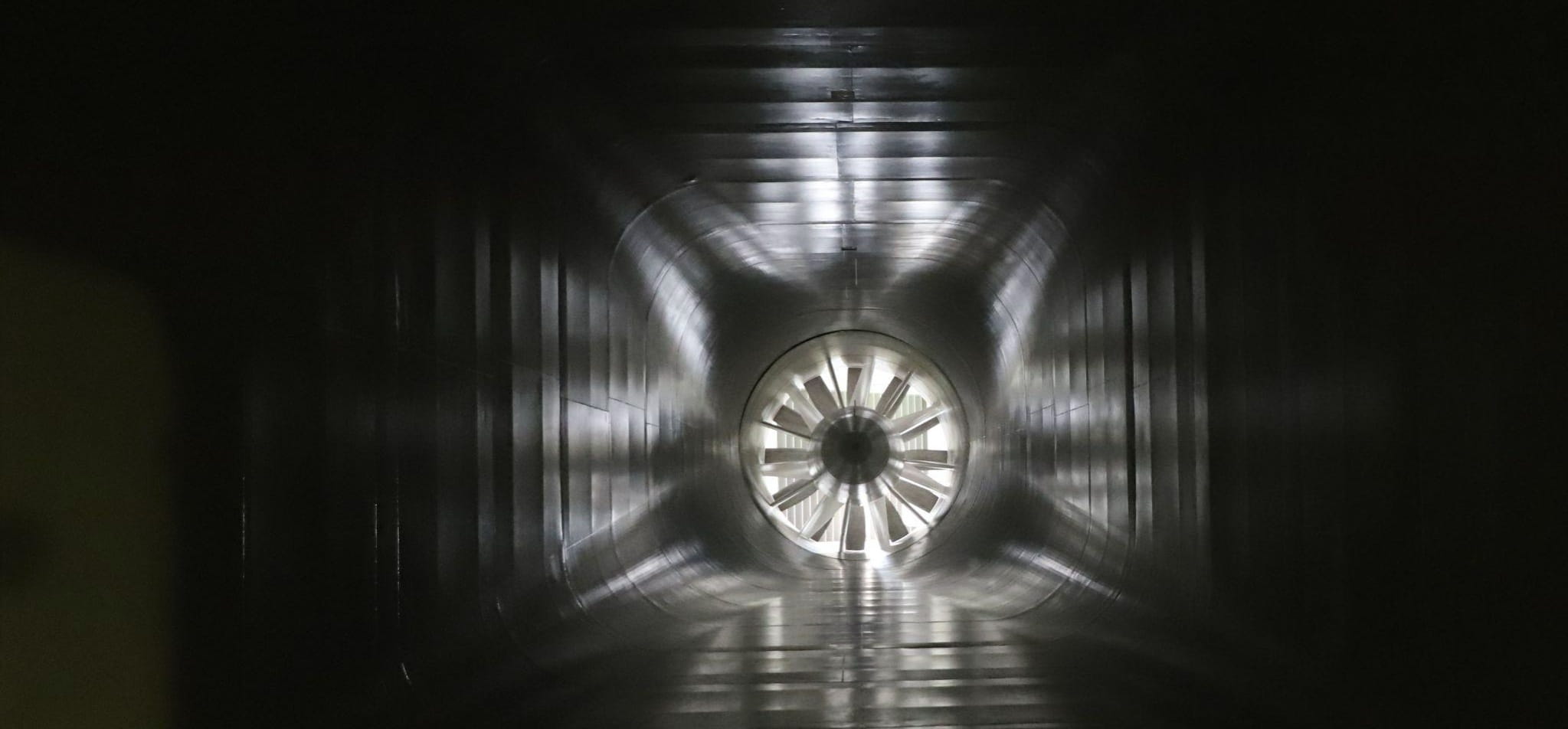

The fan powering McLaren’s Formula 1 windtunnel at its headquarters in Woking, UK

How a windtunnel works

Since so much of the performance of an F1 car depends on efficient aerodynamics - stable and high downforce combined with low car weight - aerodynamic study is paramount in developing these machines.

The most important tools for developing an F1 car’s aerodynamics are the simulator - in which drivers test a virtual version of the car on virtual renditions of real circuits - plus the use of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and the windtunnel.

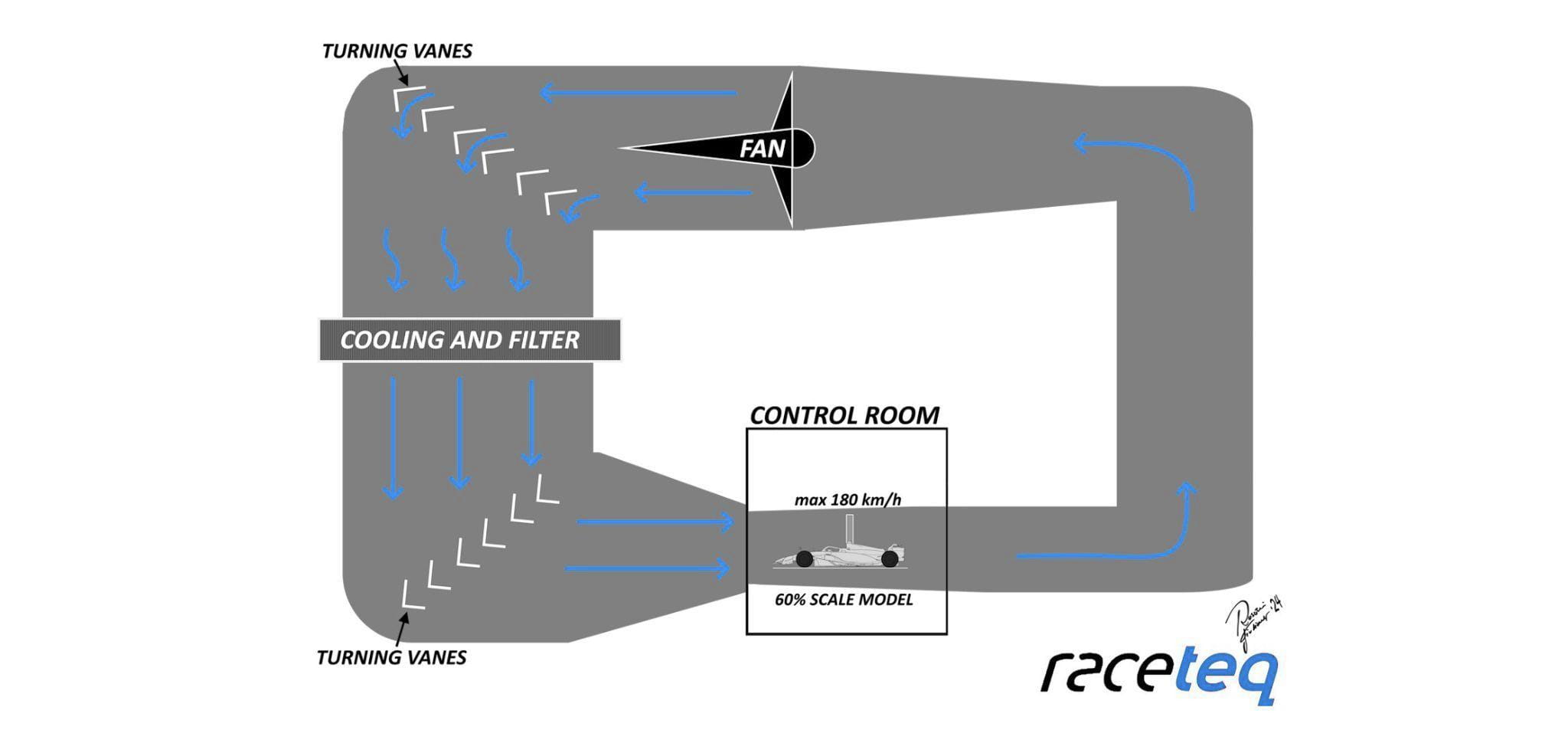

The windtunnel is essentially a large hollow tube with a massive fan at one side. This fan blows air at a scale model of an F1 car that runs over a treadmill to approximate airflow over the car’s parts. Although it’s an approximation of behaviour, teams have invested huge amounts in windtunnel development to test aerodynamic performance.

Road car companies and other motorsport teams also depend on windtunnels. Recently, Ford spent $200 million to develop a windtunnel in Michigan, US, while Honda spent a reported $124 million on its windtunnel in Ohio, US.

The $200 million Ford windtunnel in Michigan, US, supports a full-scale car on a rolling road. This tunnel was used to develop the Ford Mustang Dark Horse.

There are two types of windtunnels used in F1: closed-cycle and open-cycle. They use the same components, but the former expels air to the outside and the latter recirculates air. In F1, teams typically use closed-cycle tunnels and most teams have one of their own - although some such as RB and Haas rent them.

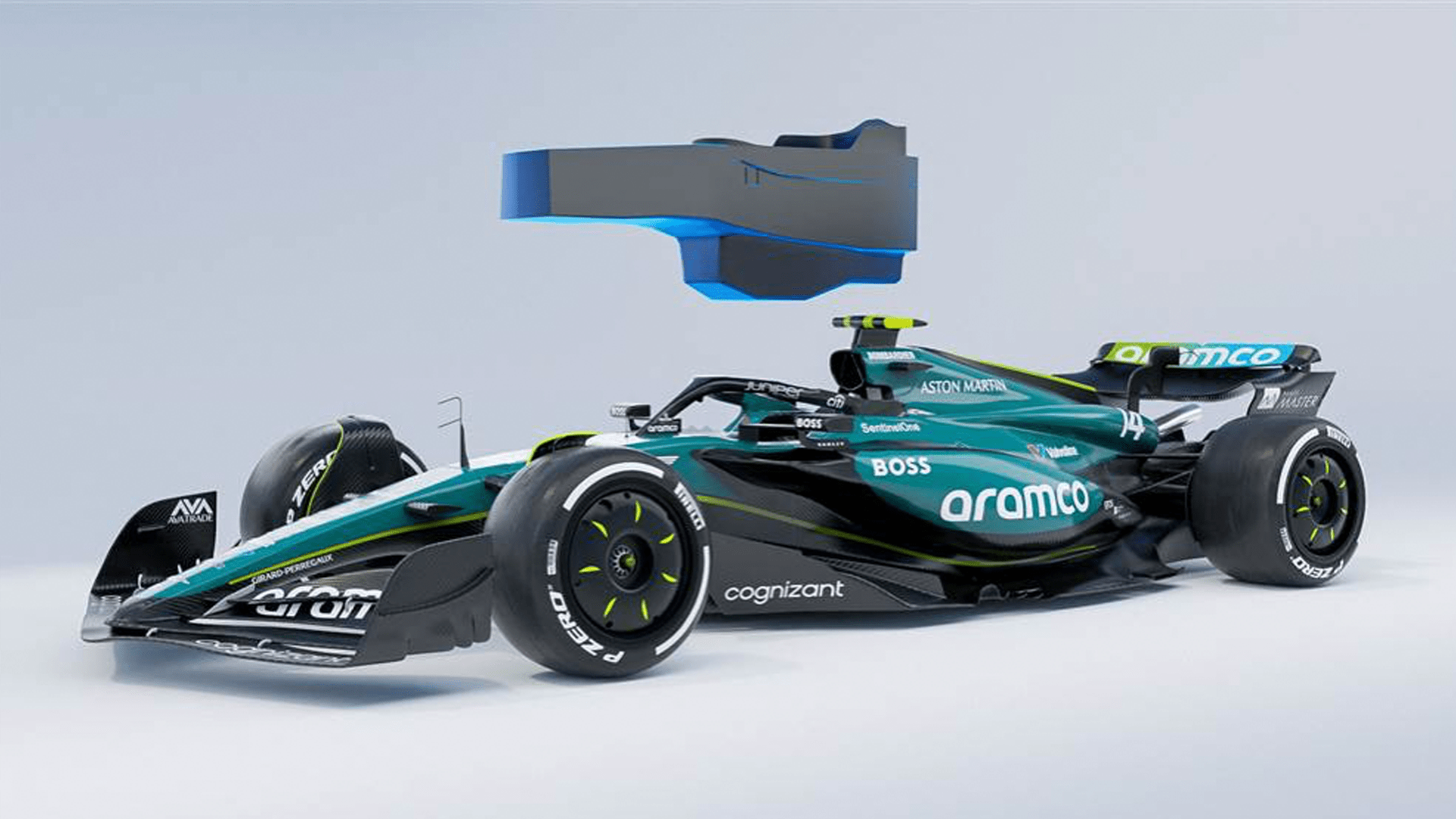

The fan that circulates air has a diameter of about five metres and a power output of around 2,000 kiloWatts (kW). A scale model of an F1 car, 60% as big as the real car, is placed inside the chamber and the tyres move on a treadmill to simulate turbulence produced by the tread moving.

The engineers sit in a control room adjacent to the test chamber to view real-time data fed by around 400 sensors fitted to the windtunnel and the scale model.

A Mercedes scale model inside the team’s windtunnel at Brackley, UK. The scale model is held up by a pylon that can control movement on multiple axes

The model is tested to simulate the various aerodynamic conditions such as yawing, rolling and pitching - a very important aspect since the latest generation of F1 cars (and Formula 2 cars) rely heavily on Venturi tunnels.

Every improvement found in the windtunnel is then translated into a tangible development that the teams can make with the various updates brought in over the course of the season. The target is also to be able to make the aerodynamic map as stable as possible in order to have a car on the track that gives a good driving feeling to the driver.

Diagram showing the layout of a windtunnel with a fan blowing air at a maximum of 180 km/h at a 60% scale model of an F1 car

What are the F1 windtunnel regulations?

The windtunnel is regulated by the FIA, with the ruling body constraining each individual team in the way it can use this tool.

Windtunnel use is regulated heavily to keep the field competitive and limit costs, but time is therefore at a premium. This means teams will mount their scale models as quickly as possible inside the windtunnel to make sure they have as much time as possible to analyse their findings.

The ATR (aerodynamic testing regulations) govern the make-up of the scale model used in the windtunnel as well as the conditions in the windtunnel. For example, the model used to test must be smaller than the real car, with a maximum size of 60%, and a maximum speed of 180 km/h.

In addition, the amount of time is heavily regulated in the FIA sporting regulations by the ATR.

Teams must also conform to the ATP - Aerodynamic Testing Period.

There are six ATPs in the year:

- Period one begins on January 1 and finishes at the end of week nine.

- Periods two, three and five run for eight weeks each.

- Period four runs for 10 weeks but comprises the summer shutdown period in which teams cannot work on the car for two weeks.

- Period six ends on December 31.

According to the regulations, “Each competitor may nominate only one windtunnel for use in any one 12-month period and declare it in writing to the FIA.”

Furthermore, a single windtunnel run is deemed to have begun when the air speed inside a windtunnel rises above 5m/s and ends when the air speed falls below 5m/s. And only two shifts of occupancy can be conducted in one 24-hour day.

For the first three ATPs of the year, teams are limited in how much time they can use the windtunnel depending on their constructors’ championship position in the previous year. For the final three ATPs of the year, teams are limited by their constructors’ championship position at the end of the final day of the third ATP of the year as per the below table.

| Championship position | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| % of windtunnel time allowed | 70% | 75% | 80% | 85% | 90% | 95% | 100% | 105% | 110% | 115% |

In this regard, teams that have their own in-house windtunnels are at an advantage as they can store their models close by and make better use of the time allowed by the regulations.

As with everything in F1, efficiency is key when it comes to using and understanding the windtunnel - but even then, things do not always go to plan.

Throughout this ground-effect era of F1, for example, teams have struggled with ‘porpoising’, and that phenomenon was not able to be simulated inside the windtunnels. It only became clear on the track, and it has been a constant issue for some of the squads.

On-track testing is therefore the best tool for evaluating car performance and the efficacy of upgrades - and this is just as strictly limited as windtunnel testing.

Without the windtunnel, however, teams would face massive uncertainty bringing their parts from the factory to the track - and this complex piece of machinery is what drives the perennial and crucial F1 upgrade race.

/image-(2).jpg?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)

/xpb_1300472_hires-(1).jpg?cx=0.52&cy=0.57)

.png?cx=0.5&cy=0.5)